An Gorta Mór: The Great Starvation

- Published in Creative Works

- Print , Email

The Irish Famine, known also as the Great Starvation and An Gorta Mór took place in the 1840’s.

The Irish Famine, known also as the Great Starvation and An Gorta Mór took place in the 1840’s.

Forty years after the fact the potato blight was diagnosed as Phytophthora infestans, treatable by spraying copper compounds and thus reduced to an agricultural nuisance. The blight probably reached Europe by way of produce in the holds of ships from America. While the potato crop was blighted, the Irish also grew barley, oats, wheat and livestock, all designated for export by the British as it was grown on land owned by English landlords. The convoys filled with this food travelled to ports under armed guard. Along the roads they passed starving men, women and children who faced prison and execution if they tried to take any of the food.

The fate of Irish peasants was in the hands of men on both sides of the English Parliament who believed in “market forces”(political economy) and many, if not most, were influenced also by the theory of Benthamite utilitarianism. Jeremy Bentham was a political reformer who believed that legislation was unjustified except where it answered a clear need to achieve the greatest happiness of the greatest number and legislated pain could be allowed so long as it promised to exclude some greater evil (the collapse of British economy). Supporters of the Corn Laws argued that if foreign grain was admitted freely into Britain and Ireland the price would collapse and millions of laborers whose livelihood was dependent upon the growing of grain would go without work. The Corn Laws put the price of local grain at the highest level to keep out other cheaper grain (rice and Indian corn) until the entire British crop had been sold at the artificially higher price. Thus, in the name of greater possible evils, Ireland’s pain was sanctioned, even championed, by many in Parliament.

The fate of Irish peasants was in the hands of men on both sides of the English Parliament who believed in “market forces”(political economy) and many, if not most, were influenced also by the theory of Benthamite utilitarianism. Jeremy Bentham was a political reformer who believed that legislation was unjustified except where it answered a clear need to achieve the greatest happiness of the greatest number and legislated pain could be allowed so long as it promised to exclude some greater evil (the collapse of British economy). Supporters of the Corn Laws argued that if foreign grain was admitted freely into Britain and Ireland the price would collapse and millions of laborers whose livelihood was dependent upon the growing of grain would go without work. The Corn Laws put the price of local grain at the highest level to keep out other cheaper grain (rice and Indian corn) until the entire British crop had been sold at the artificially higher price. Thus, in the name of greater possible evils, Ireland’s pain was sanctioned, even championed, by many in Parliament.

In addition, leaders of both sides of the House subscribed to the theories of Rev. Thomas Malthus, the population theorist, who had written a considerable amount on Ireland, a country he had never visited. Malthus said, “…the land in Ireland is infinitely more peopled than anywhere else; and to give full effect to the natural resources of the country a great part of the population should be swept from the soil.” An Irish catastrophe was considered inevitable by the leading Whigs and Tories and though few would actually say it until the disaster was well advanced, was even desirable.

So, the Great Hunger, whatever its other causes, was seen as a visitation upon the Irish themselves, a remedy for their over-breeding and their over-dependence on the potato.

From The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Nan A. Talese, an imprint of Doubleday, a division of Random House, New York, 1999 and Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy and Memory, Cormac O’Grada, Princeton University Press, 1999.

Report by William Bennett on conditions in County Mayo: Belmullet, County Mayo, 16th of third month, 1847:

Report by William Bennett on conditions in County Mayo: Belmullet, County Mayo, 16th of third month, 1847:

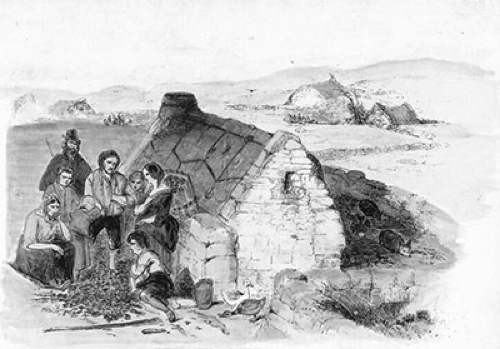

“We now proceeded to visit the district beyond the town, within the Mullet. The cabins cluster the roadsides, and are scattered over the face of the bog in the usual Irish manner where the country is thickly inhabited. Several were pointed out as ‘freeholders’; that is, such as had come wandering over the land, and squatted down on any unoccupied spot, owning no fealty and paying no rent.

"We spent the whole morning in visiting these hovels indiscriminately, or swayed by the representations and entreaties of the dense retinue of wretched creatures, continually augmenting, which gathered round and followed us from place to place, avoiding only such as were known to be badly infected with fever, which was sometimes sufficiently perceptible from without by the almost intolerable stench.

"The scenes of human misery and degradation we witnessed still haunt my imagination with the vividness and power of some horrid and tyrannous delusion rather than the features of a sober reality. We entered a cabin. Stretched in one dark corner, scarcely visible from the smoke and rags that covered them, were three children huddled together lying there because they were too weak to rise, pale and ghastly; their little limbs, on removing a portion of the filthy covering, perfectly emaciated, eyes sunk, voice gone, evidently in the last stage of actual starvation. Crouched over the turf embers was another form, wild and all but naked, scarcely human in appearance. It stirred not, nor noticed us.”